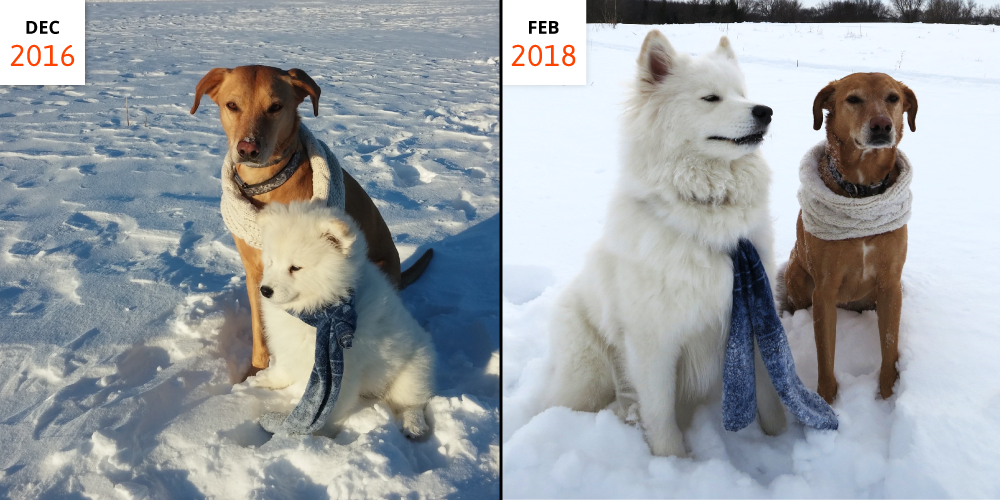

If you have been following Filament Games you have probably met my dog Euler (named after Leonhard Euler). As you might infer, Filament has an office policy where pets are welcome at work. Euler has appeared across Filament’s media. For example, she has been featured, and photo-bombed others on our instagram. I added a second dog, Pythagoras, to my family in December. She has grown into adulthood, and in addition to being immortalized by Natasha’s artwork, it is time to get serious about her obedience training.

I had a professor explain that game design is about crafting an experience, and he committed himself to be conscientious of everything that he experienced – not just other forms of entertainment. He was very passionate about inspiration coming from anywhere. Additionally, being immersed in critical thought honed his design. Even something as banal as traversing an airport was an opportunity to reflect on what worked well and what was confusing.

I have tried to take the same approach of analyzing and reflecting on any experience I have that involves learning (though admittedly it is tougher for me because I do not have a formal background in education). As an engineer, no one is ever going to ask me to design pedagogies, but it is an important skill to develop in order to better understand our users’ needs and build more effective products. My most enlightening experience to date has been dog training.

Attention is everything. If you can’t get your dog’s (or your target audience’s) attention it is hopeless. You have to do whatever it takes: physical attention, putting a treat in their face, skipping a meal to make those treats more exciting, clapping your hands, or saying your dog’s name. When Euler was young and unable to focus what worked was picking her up off the ground. Every dog is unique. At home you can create a controlled environment free of distractions but what you are training for is the real world. You are training for the moment when your dog goes to chase a squirrel across a busy street. Finally, learning to pay attention is a learned habit – at least with dogs.

In the games industry, instead of “attention”, we will use the word “engagement” or “interest”. Game developers, just like a storyteller, try to craft an experience so that interest is maintained throughout. We can’t create a memorable experience that changes people’s lives if they stop playing.

Many tasks in life are accomplished by breaking things down into small steps, dog training included. It can be very hard to empathize with your audience when they are below your skill level, and it’s easy to assume knowledge and skip over important steps. It also takes a lot of patience to slowly work through what you are trying to teach.

I lacked an appreciation for just how granular and accessible I needed to be when educating my dogs. When first learning a new command, most of the time there isn’t any exception on behalf of the dog. Sit, stand, down, and bow all start with you putting your dog in that pose, saying the command, and rewarding them as long as they do not move. Teaching paw / shake is initiated by holding your dog’s paw and saying the command. Training “touch” begins with you touching your dog’s nose. From these rudimentary beginnings – with a lot of repetition, encouragement, and consistency – incremental progress can be made.

I’ve talked about the importance of feedback, and with dogs it might be tempting to just think about feedback as rewards or treats – but that is an oversimplification. There are some behaviors, like jumping up on you, that you break by not giving any feedback or by giving negative feedback (with dogs sometimes any reaction is positive reinforcement). Even in the case of your dog displaying desired behavior, it is best to give multiple forms of feedback. For example, audible praise helps bridge the gap in time before you can put a treat in your dog’s mouth.

Much of dog training relies on the trainer coaching their dog with appropriate feedback and knowing when to move through learning stages. Early on in learning a new skill there is high praise and rewards for anything close to what you were asking – you are trying to make a memory. Then you go through a period of consistent rewards to reinforce the association. Once the connection has been made, you can move to refining the command by becoming more strict, you stop rewarding flawed attempts but jackpot perfect practice. Then you ramp up the difficulty by adding it to a sequence of commands, increasing your distance from your dog, increasing the length of time they need to hold the command, or adding the challenge of a distracting environment.

Challenge progression and reward cadence are essential components of any game’s design. Usually they will be referred to under the umbrella term “flow” originally coined by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. After we gain the user’s attention, balancing challenge and rewards are how games keep players motivated to continue playing – it is what makes practice engaging.

It would be a mistake to directly apply my dog training models to people, but it did prove to me that there are universal rules for learning that even cross the species divide. A dog isn’t going to learn unless you create a rewarding, challenging, and pleasurable experience for them. People are a bit more willing to take the long view and slog through the rigors of learning – but we have to ask ourselves how many more people can master skills if we reduce learning friction.

I’ll leave you with the words of one of my favorite game based learning philosophers:

“In every job that must be done, there is an element of fun

You find the fun and snap, the job’s a game”