When I was hired here at Filament five years ago, I had a lot to learn. Back then, the first tool I learned was Flash. You remember Adobe Flash, right? In recent times it has put on a new logo and has been masquerading around as “Animate CC” but lo, it is the exact same program, only more relevant-sounding to these modern times. I had only used Flash once prior to my career, experimentally and not in any structured course in high school or college. Navigating Flash’s interface was the least of my worries though; in truth, I had absolutely no idea how games were even made. A lot has changed in five years.

As a newborn game artist, with coaching and supervision from many of my coworkers, I managed. Every game I worked on since starting at Filament, for three years, was made in Flash. Even after we started making games in HTML5 and Unity, our art was created in Flash. It’s just what we game artists knew how to do, and it’s what (we thought) looked good.

Flash, a vector program, differed from raster programs in that it had a relatively intuitive timeline at the ready, and its nesting capabilities allowed us to set up innumerable character rigs for animations. It was the fastest, most sensible solution.

Now let’s return to that keyword: vector. Vector artwork is invaluable in that it can be stretched or shrunk to any size without losing its fidelity: great for printing and zooming-in! It keeps strokes (lines) separate from shapes (color fills), and editing the shape of an object is as simple as dragging a single vector point.

The flat game assets, often made shiny and poppy-looking with gradients and bright colors, successfully looked like game assets, and they certainly had their charm. But there was a static impression that we couldn’t shake with any amount of bounce or sway in its idle animations. Filament’s game artists have always held the primary title of illustrators; when it comes to game art, we have a strong historical preference for hiring illustrators. Put a computer mouse in our hands and we can turn any object or character into a vector asset, we know the tool, we can do that! But put a digital pen or stylus in our hands and we’ll bring those objects and characters to life.

Raster programs like Photoshop, Paint Tool SAI and Clip Studio Paint don’t exactly scream “WELCOME TO THE FUTURE, MAKE A GAME WITH EASE!” The game assets we draw or paint have to go through some levels of processing before it can actually make it into the game editor (typically Unity). It’s a few steps removed from the natural flow of creating game art in its native editor, but as we push game after game out the door, we find it’s worth the effort. We illustrators are even starting to take the extra steps out of our comfort zones to dive into the game editor itself – we have to if we want to animate our characters or take ownership of dazzling particle effects. Technology has come a long way, and we’re all still learning to adapt to it.

In addition to the tech, five years of practicing doing what you love can bring you a ways. All of Filament’s artists, both illustration and UX, learn something new on every project. What we take away from the last project, we apply to the next, be it brush textures, lighting stylization, animation effects or pipeline efficiencies–the list goes on. As the studio delves more into 3D and VR games, I am eager to find out what our team can learn in the next five years.

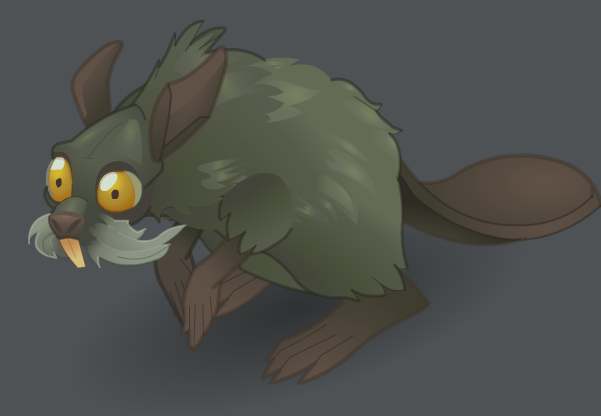

“Mudweaver” from The Radix Endeavor, Adobe Flash, 2013 (about 3 hours)

“Mudweaver” redrawn, Adobe Photoshop, 2017 (about 45 minutes)

More articles from Artist Extraordinaire Natasha Soglin:

Speed Sketch! Styles for All Ages

Art Hacks: Line Art from Pencil to Screen

Art Hacks: Shading Made Easy