Happy (Almost) National Poetry Month! We’ve touched on the fine arts and video games on the blog before, from music learning games to simulated art galleries. However, I know what you’re thinking from looking at the title of this post – what could poetry possibly have to do with video games? Do video games and poetry intersect at all? If you think the answers are nothing, and no, respectively, I invite you to read on!

via Giphy

Poetry and Play

Before we get too far into the relationship between poetry and video games (and the potential for learning found there!) I want to note that we’ve briefly discussed a video game about poetry before. In our post on Student-Created Educational Games, we highlighted Underdepth, created by Molly Hanna and Noah McFarlane – two University of North Carolina students in Professor Gabrielle Calvocoressi’s Poetry Stylistics and Professor Courtney Rivard’s Storytelling and Game Development courses. Teaching these courses parallel to one another, the two professors challenged their students to experiment with poetry and play. Underdepth was one of the results of this collaboration – a game that features a branching storyline about crisis and loss and elements of renga, a Japanese poetic form.

via englishcomplit.unc.edu

Perhaps to those who don’t frequently engage with poetry (beyond the required reading of Shakespeare and Robert Frost in high school English class) the idea of poetry and play may seem strange or contradictory. After all, aren’t most poets supposed to be serious, writing about mortality, landscape, or their deepest, innermost thoughts? Isn’t poetry supposed to make us sit back and see life in a whole new way, uncover a new depth of feeling, as we ponder it during momentous occasions in our lives, like graduation ceremonies? Two roads diverged in a yellow wood. I have news for you if “The Road Not Taken” was read at your graduation. It was written as a joke.

While not all poems are written as jokes, I’d argue that they all incorporate an element of play. Whether that’s in the process of writing or reading them aloud or on the page. When I was pursuing my Master of Fine Arts in poetry at Ohio State, I became obsessed with the pantoum, a poetic form that takes certain lines throughout a poem and repeats them in a specific pattern, like weaving. Poetic forms are a way to play with language. Whatever I was writing about, no matter how serious, while drafting poems I was playing with language – from elements as broad as narrative and as granular as punctuation or alliteration. I’d go as far to say that it’s a poet’s job to play with language, restricting ourselves with rules and boundaries, or sometimes the opposite, breaking as many rules as we can as we go along. In and of itself, writing poetry is playful, is a game, which is one of many reasons I am drawn back to it time and time again.

Are Video Games and Poetry Even Compatible?

We’ve established that poetry inherently involves some kind of play. Excellent! But does that mean that that play can be translated into video games? Does poetic language integrate naturally with the aims of video games, or does it oppose it? That’s exactly what poet, editor, and interdisciplinary researcher Jon Stone set out to understand in his article, “Separation Anxiety: Plotting and Visualising the Tensions Between Poetry and Videogames”. More specifically, Stone wants to investigate claims from humanities scholar Astrid Ensslin and digital poet Jim Andrews that poetry games are intrinsically paradoxical, and go together like “oil and water.”.

Stone writes that while language games (like Twine and Bitsy) are by no means the most popular video games, they are emerging more frequently than they used to. He refers to Ensslin’s book, “Literary Gaming” to define “poetry games”: “Poetry games, according to Ensslin, are videogames which replace one or more traditional features of games with poetic language — language that draws attention to its own structure and aesthetics.” In other words, poetic language is integrated into the center of a game, becoming a main focus. Stone continues on, asking a reader to suspend commonly held beliefs on the purpose of video games: “Rather than thinking of the gameplay experience in terms of winning, losing or accumulating, we can comprehend it as a space in which the player becomes enmeshed with various layers and dimensions of the virtual, potentially with other players as well. In theory, then, could the text of a poem not serve as one element of this enmeshment?”

Whew, I know this may be getting heavy, but stick with me! Digital space is a place we can inhabit while playing a game. While not entirely made up of our imaginations, we have to put aside our realities while playing to become fully immersed. I would argue that poetry does a similar thing – the words act as a vessel for the reader to become immersed in someone else’s mind, a different landscape, whatever the poem’s subject matter – for the duration of reading it. Is it possible to mesh digital spaces with literary imagination?

Stone’s Three Continuums

Stone investigates the compatibility between video games and poetry further through three continuums, the first of which he calls “text versus cybertext.” Put simply, cybertext refers to a text or narrative that a reader must actively participate in. Think of “choose-your-own-adventure” books and “choices matter” narrative games. The narrative is shaped by the user’s choices, and it is dependent on the user to move it along in a specific direction.

To define “text” in this context, think of a novel, or an action movie. A reader or viewer is passive, nothing they do can change the course of the narrative. On Stone’s continuum below, text is on the left while cybertext is on the right.

via gamestudies.org

To further illustrate his point, Stone gives us many examples on this continuum, which you can see below.

via gamestudies.org

While it might be tempting to place poetry on the left as a text, and video games on the right as cybertexts, we can see from Stone’s examples that it isn’t so cut and dry. Stone references a few games in his article, such as Silent Conversation, that involve a player reading a poem within a game, and in those cases, the tension is clear – a text is being placed into a cybertext. Writing poetry, however, is a cybertextual experience, and so games that involve writing poetry rather than reading it may negotiate these two ends of the spectrum more naturally.

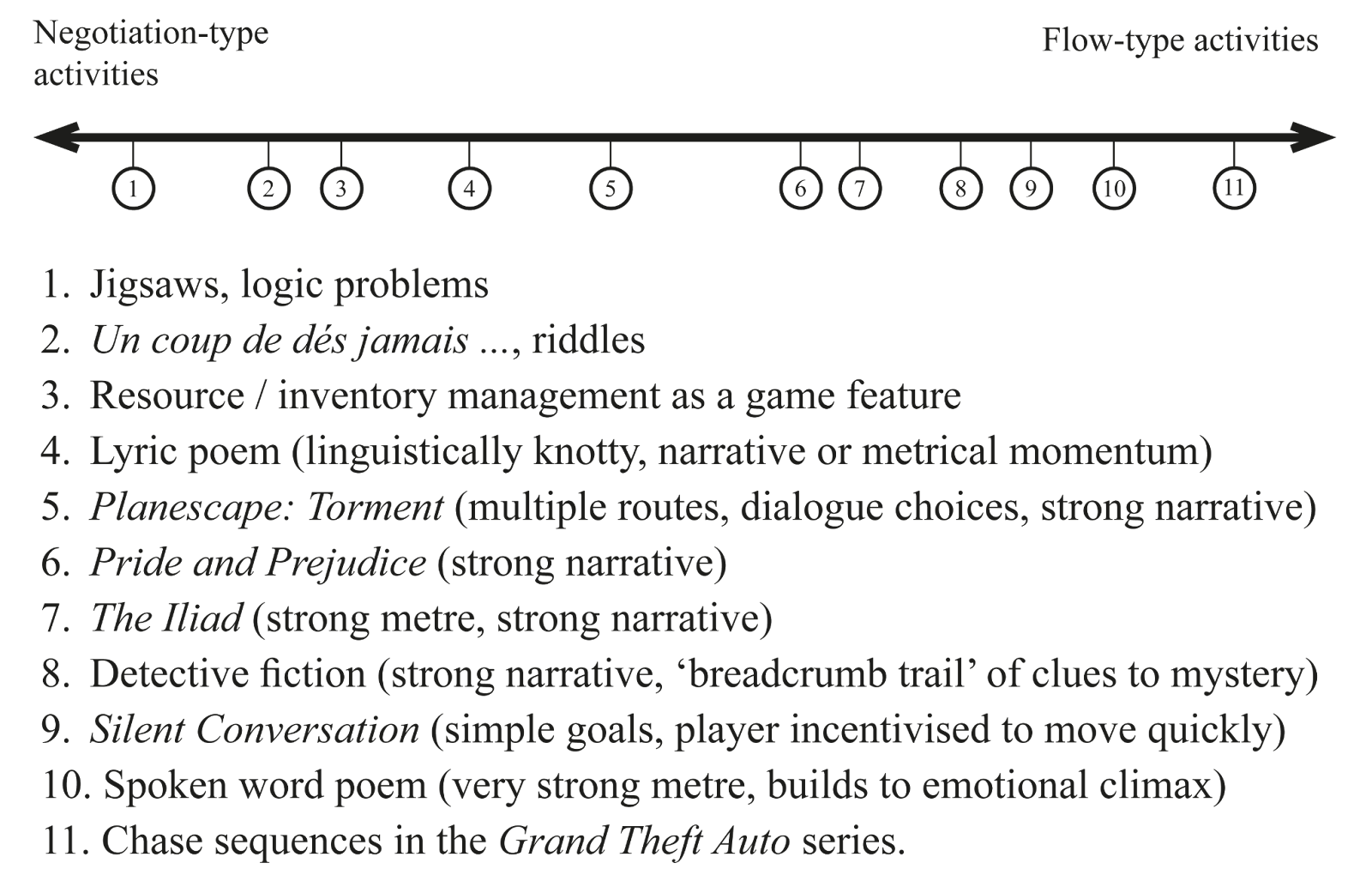

Moving on to Stone’s next continuum: “deep attention versus hyper attention.” To define these two terms, Stone turns to postmodern literary critic N. Katherine Hayles. “Deep attention is characterized by Hayles as ‘concentrating on a single object for long periods … ignoring outside stimuli while so engaged, preferring a single information stream, and having a high tolerance for long focus times’”, while “Hyper attention, in contrast, is characterized by ‘switching focus rapidly among different tasks, preferring multiple information streams, seeking a high level of stimulation’ and associated with the use of computers and digital media, including social media.” In other words, deep attention is when one gives their undivided attention to a single task, and hyper attention involves multitasking, pivoting from one idea to another. Stone, believing there to be more complexity in this particular context, defines his own continuum based on the ideas of deep attention and hyper attention. He writes, “I propose… a second continuum that runs from ‘negotiation’ as the dominant form of reader/player interaction — meaning the demand that a conscious effort be made to examine the components of a text so as to make sense of them — to, at the other extreme, continuous emphasis on achieving ‘flow,’ where a reader/player is able to lose themselves in the fast-moving current of events.” In simpler terms, this spectrum examines how much critical thinking is needed to engage in the activity.

via gamestudies.org

Stone believes “that videogames are equipped, technologically and phenomenologically, to absorb players more deeply over a longer period” and questions “whether these powers can be used in conjunction with the kind of attention poetry commands, or whether the two are irreconcilable.” Based on the diversity of examples Stone builds out on this continuum, he concludes that “When we look at the sheer variety of ways information streams are combined in videogames and the subtle variations in the styles of engagement they solicit, it is difficult to see why literary content should stand out as presenting a unique problem.” Seeing as how both games and poems run the gamut between negotiation and flow, it’s easy to see how this is not a conflict of interest between the two creative mediums. The predictability and sheer sonic pleasure of a poem heavy with meter and rhyme align with an instincts-based task in a video game, while reading lyrical or free-verse poems requires critical thinking and juggling multiple concepts at once, just as logic puzzles and resource management.

Stone’s final continuum is “rules versus irresolution.” This continuum is pretty self-explanatory, running from “irresolution dominated” content, such as concrete poetry and free-verse lyric poetry to “rule dominated” content such as BioShock and a driving simulator. This continuum maps how many rules and goals are set for the user, versus content where the user makes up their own system of rules and goals. Here, we can see the tension between poetry (especially free verse) and video games: subjectivity as opposed to objectivity, meaning creation (or lack thereof) versus clear, already existing meaning.

via gamestudies.org

Through these three continuums, Stone maps out the tensions and the compatibility between video games and poetry, trying to see where they may naturally integrate and where they repel one another. Stone writes that these three continuums explain the rising popularity of language building games and tools: “Taken together, these three continuums not only articulate precise tensions between poetry and video games that developers of poetry games need to negotiate, but also explain why tools like Twine and Bitsy have become popular as a means of experimenting in this area, beyond their ease of use. Rule-dominated systems that articulate their values in the form of procedural rhetoric, especially those that enforce speedy decision-making and which are designed to induce a state of flow, make it difficult for the player to enter an interpretative, critical or reflective state and therefore to meet the intellectual demands of poetry.” I know what you may be thinking now – all these continuums, and still no clear answer as to whether video games and poetry are compatible?! That’s right – Stone’s conclusion is slippery, just like the nature of, well, continuums (and poetry itself).

In short, his answer is that it is challenging to integrate the two. However, he does note that he thinks developers will come up with innovative solutions in the future to even better integrate poems and video games. He writes, “I have not addressed in this article, for instance, examples of video games that attempt to embody the poetic not through integration of poetic language but through paratactically expressive visual and mechanical design.” While poetic language and video games may require several opposing ways of thinking and understanding, this isn’t to say that poetry can never serve as some sort of game art or mechanic. That’s still an area to explore within game design!

Poetry in Video Games

With the above exploration of poetry and video games being mostly theoretical, let’s take a look at a few concrete examples of video games that include poetry, and see how the developers brought the two together.

via futureproofgames.itch.io

This game was a catalyst for the Jon Stone article we broke down earlier. But let’s get into the nitty-gritty: what exactly is this game? Created by Future Proof Games, this side-scroller requires a player to run and jump through words – words that make up poems and stories from authors such as Basho and H.P. Lovecraft. At times, the landscape of the game is made up of poems, allowing a user to experience a poem as they play. Some may argue that this distracts a reader from fully understanding a poem, or rushes them through it; though others may see it as a way to immerse themselves in writing without getting caught up in dissecting the meaning.

Ichiro Lambe and Ziba Scott’s Elegy for a Dead World takes a player through three different worlds, each one inspired by a different British Romance-era poem. Players experience the developer’s visual interpretation of “Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley, “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be” by John Keats, and “Darkness” by Lord Byron. This game also uses both landscape and narrative as writing prompts, drawing on poetic traditions of ekphrasis and “conversing” with other poems by writing in response to them. Essentially, the game is played by writing about it.

Poet Victoria Bennett and her partner, digital artist Adam Clarke, used the popular sandbox game Minecraft to create a visual interpretation of Bennett’s poem, “My Mother’s House.” The couple told Alphr reporter Thomas McMullan that “the original Italian meaning of stanza is ‘room’, or ‘stopping place’’” and so Bennett and Clarke gave the poem digital rooms in Minecraft. In this case, a poet is creating a structure in a game alongside the structure of a poem to create something that enhances the experience of both.

Whether a game is immersing a player in words, using digital landscapes as writing prompts, or turning stanzas into digital rooms, developers are finding the places where poetry and games interact in all sorts of interesting ways.

Video Games as Poetic Inspiration

While poems can be built into video games, video games can be used as a tool in the creation of poems. Ekphrasis, a term I mentioned earlier, is the practice of writing based on a piece of art – and the definition of “art” extends to video games. And there’s no shortage of writers that find inspiration for their work through games. Publications like Cartridge Lit are dedicated solely to writings inspired by video games. Several video game poetry anthologies have been published in the 2010s and 2020s, such as Hit Points and Coin Opera 2: Fulminaire’s Revenge. Poets can find inspiration in open-world games, such as streamer Niall O’Sullivan who gathers inspiration for his poems through titles such as Breath of the Wild and Red Dead Redemption 2 (and he writes these poems live on Twitch!).

An Eclectic Past and an Exciting Future

It may be evident from the length of this post, but there is so much more to say about poetry and video games than a lot of people may think when they consider the two subjects in tandem. Though not every video game is a great vehicle for poetry, and not every video game leaves room for players to wax poetic, it is undeniable that they have interesting friction. There is no one way to combine the two, and certain ways to put video games and poetry together may fail while others succeed. That leaves an exciting space for developers to work in, to collaborate, and ultimately, to exercise creativity. There’s so much uncharted territory when it comes to poetry and video games, and on the rare occasions the two do come together, it may not be perfect, but it is sure to be fascinating.

To close out, check out this panel on “Games as Poetry, Poetry as Play” from Freeplay 2021, where a panel of multidisciplinary creatives discuss the function of poetry in games, how games and poetry inform one another, and more.

Looking to create your own educational game? We’d love to hear from you!

More on video games, reading, and writing: