“Oh right! And…sorry…no you…uh, I was just… no you go first, go ahead.”

“I was just saying that bSHHHTZTK in the first place.”

“Sorry, could you repeat that?”

Today’s high speed fiber optic networks and teleconferencing technologies connect people and businesses across the globe in seconds, but what are the affordances and limitations of this new medium, and how can we use it well? Does it really enhance communication or does it create more opportunities for miscommunication? In this three-part blog post I’d like to shed light on how Filament approaches remote collaboration and telecommunication and also touch on some of the tricks of the trade that help us keep pace with the ever-changing technology.

But first! As a bit of a history buff and a pretty big geek when it comes to telecommunications technology, I would like this first article to serve as a fun historical primer on the topic. (We’re here to create useful learning outcomes, after all!)

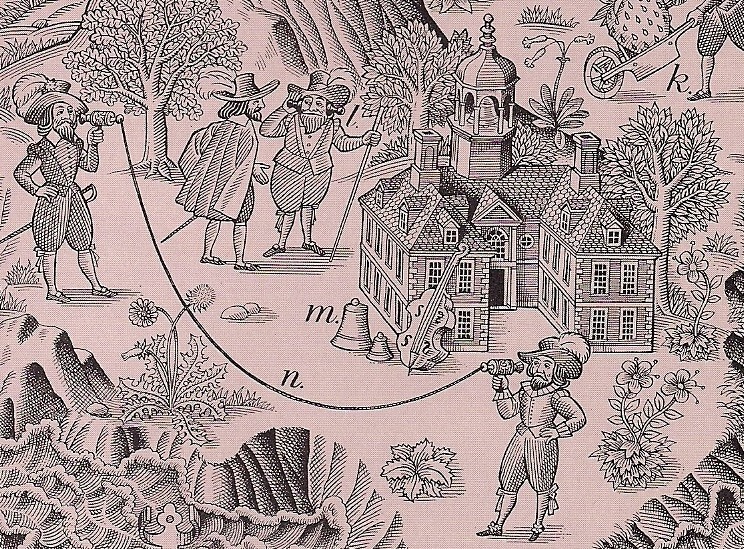

Strange Lines and Distances

For hundreds of years we have been imagining a connected world where our voices knew no bounds. In Sir Francis Bacon’s The New Atlantis in 1627, he imagined an advanced society with sound houses where, “We have also means to convey sounds in trunks and pipes, in strange lines and distances.”

In Bacon’s time, the distance of communication was limited to what the human eye could see and optical telegraphy like semaphore networks were at the cutting edge. That all changed as electricity became more thoroughly understood and Bacon’s “strange lines” were realized in the proliferation of the electric telegraph.

“What hath God wrought!” declared the first(ish) message sent over Samuel Morse’s single-wire telegraph line from Washington DC to Baltimore in 1844. Indeed, this new technology was exciting, but not long after, Alexander Graham Bell offered his (hotly disputed) patent for the acoustic telephone to Western Union for a steal, and they turned it down, thinking it was just a novelty. Oops.

In 1926, Nikola Tesla offered his own flash of imaginative forward thinking when he presciently spoke of what we would now call a smartphone. “We shall be able to communicate with one another instantly, irrespective of distance. Not only this, but through television and telephony we shall see and hear one another as perfectly as though we were face to face… and the instruments… will be amazingly simple compared with our present telephone. A man will be able to carry one in his vest pocket.”

You nailed it Nikola, today pocketed vests are all the rage in men’s fashion and video chat and smartphones have indeed become ubiquitous. Telecommunications technology has indeed come a long way, but is it really as though we were face to face? As evidenced by my very cheeky intro I would argue that no, it is not.

The Medium is the Massage

In the early telecommunications systems like Morse code and semaphore networks, each system contained a language of its own as byproduct of the medium of communication. In 1964 Marshall McLuhan wrote about this concept still present in our high-fidelity forms of communication with his famous statement, “the medium is the message.” Meaning, the medium we use to communicate shapes/transforms/distorts the content being communicated. For instance, if I am trying to convey a message, I would use a very different mode to do so when speaking at a conference vs. writing for a blog vs. producing an educational video game. Additionally the reception of my message would be very different via each of those different media.

Today the telecommunications technologies we regularly use resemble face-to-face communications, but they do not afford the immediacy, intimacy, and presence necessary for the many nuanced expressions (vocally and through our body movements) to which we are accustomed. In the next installment of this article I will address how Filament navigates the limitations of these telecommunications media and utilize them to build healthy and communicative relationships. But to close out this primer on tele-technology I want to leave you with an anecdote from my time as a network music researcher.

Using high speed fiber optic research networks like Internet2 and GEANT, university music technology programs have been experimenting with performing music over a network for many years now. The fidelity of the audio used in these systems is better than CD quality and travels as fast as fiber optics can carry it, striving to be as close to true telepresence as possible. A few years ago I was working on composing a percussion piece that was to be performed between myself in Calgary, AB and a young student in Beijing, China. The piece was designed to use the network delay (around 180ms) as a rhythmic device that offset our patterns (more on that here for the curious) and it had some pretty tricky licks. He and I both were stumbling with some of the tougher sections at times and I will never forget one of the moments that arose.

We had just stopped at a rehearsal mark to try a section over again, and as if he were standing right there I heard the student give a subtle frustrated sigh, a reassuring sniff, and a re-focussing shuffle of the sheet music on his stand. It gave me chills. I couldn’t speak his language, nor could he speak mine, but we were working together, sharing our struggles and successes, to accomplish something challenging.