As educational game developers, it’s our responsibility to ensure that the experiences we create are accessible and relatable to all students. Here at Filament, we believe that all learners should have access to meaningful educational opportunities, regardless of their identity, ability, or demographics. In order to support this goal, we consider a wide range of perspectives when designing our learning games.

In this blog series, we’ll explore the different design considerations that go into making inclusive learning games. Today, we’ll be laying out an overview of the basic principles for appealing to a diverse audience. In future entries, we’ll provide practical recommendations for supporting a variety of players, including how to effectively represent marginalized identities, how to design for children with physical and cognitive disabilities, and how to support English language learners. Our goal is to empower everyone to think more critically about inclusivity in the games they create and play.

Today’s first installment will focus on the basic building blocks – the “what,” “why,” and “how” – of designing inclusive games.

What is an inclusive game?

Creating an inclusive game involves more than adding a cast of diverse characters. Inclusive games, at their core, are experiences that are designed from the ground up to be accessible to everyone – through mechanics, messaging, and user experience.

When considering how we evaluate a game’s inclusivity, I am proposing the following definition:

An inclusive game is a game that actively welcomes all players.

I chose this definition because it describes what an inclusive game needs to do without dictating a certain structure for the game itself. An inclusive game can look like anything, as long as it is designed explicitly with diverse audiences’ needs in mind.

Why does inclusive design matter?

When students connect authentically with a game, they’re much more likely to engage with its educational content. Conversely, when students can’t physically play a game, or don’t see characters that look like them, they feel isolated and miss out on beneficial opportunities to learn and collaborate. We maximize the impact of our learning games by ensuring that they’re accessible, empowering, and representative for every student.

How: Three Pillars for Universal Design

When we create inclusive games, we consider a wide variety of player demographics including physical ability, cultural background, race, socio-economic status, native language, gender identity, learning ability, game literacy, and many more. In order to create games that welcome everyone, we must actively consider how all players’ needs are supported throughout the design process, paying special attention to how their identities and perspectives may influence their experience with the game. This process is called universal design.

In learning games, universal design starts by creating mechanics that appeal to a wide audience and allow all players to feel capable. This is different from accessibility, which involves ensuring the game is usable for players with disabilities (we’ll cover that in a future installment). When figuring out the overarching play structures for a new game, I like to incorporate the following three pillars to ensure that the design is appealing and supportive to all audiences.

Pillar #1: Give players a way to create something.

The video game climate is saturated with games about destruction. However, I firmly believe that the most interesting and successful learning games are about construction – encouraging players to create things rather than destroy them.

In the education space, we’ve seen platforms like Minecraft and Roblox achieve wild success, primarily because they provide players with the space to build their own content. These games are able to appeal to a wide audience because they empower all players to express themselves through their creations, rather than asking everyone to connect with one narrow, prescribed experience. In addition to providing an avenue for self-expression, constructive games promote more critical engagement with learning content – creating original work is the highest order of thinking in Bloom’s Taxonomy. When considering constructive mechanics, think of verbs like grow, create, build, or discover.

Pillar #2: Promote collaborative play.

One of the biggest requests we get from kids during classroom playtests is to “add multiplayer.” With the rise of online games like Fortnite, kids’ schema for games is deeply intertwined with social interaction. However, we have to be incredibly careful when adding multiplayer mechanics to educational games.

While competitive games may be exciting to some students, they often alienate those with less confidence or gaming experience. Instead, we find more success incorporating multiplayer through cooperative, pro-social mechanics. In contrast to pitting students against one another, cooperative games encourage students to share their knowledge with each other, promoting equity through collaborative problem-solving. In single player games, creating experiences that ask guiding questions or require puzzle-solving will often encourage students to talk to one another.

Pillar #3: Provide a friendly learning curve.

A term you’ll hear often during a typical day at Filament is “onboarding.” Onboarding is a term used to describe the support that players receive when they first open up a game. (This is different from scaffolding, which is the term we use for introducing new mechanics and content gradually over time). Onboarding includes the game’s tutorial, but also covers deeper questions like: What does the first sequence of levels look like? How do players practice skills as they’re introduced? How do we make sure someone understands the game before we present them with tougher challenges?

Good onboarding is critical for including students that may have less game literacy or grasp of the learning content. When planning a game’s onboarding, it’s never safe to rely on players’ assumed experience with game archetypes or interactions. Instead, good onboarding starts from scratch by introducing all concepts in a welcoming, easily digestible format. This gives students support to figure out the game in a risk-free environment and build confidence early.

Inclusive Learning Games in Action

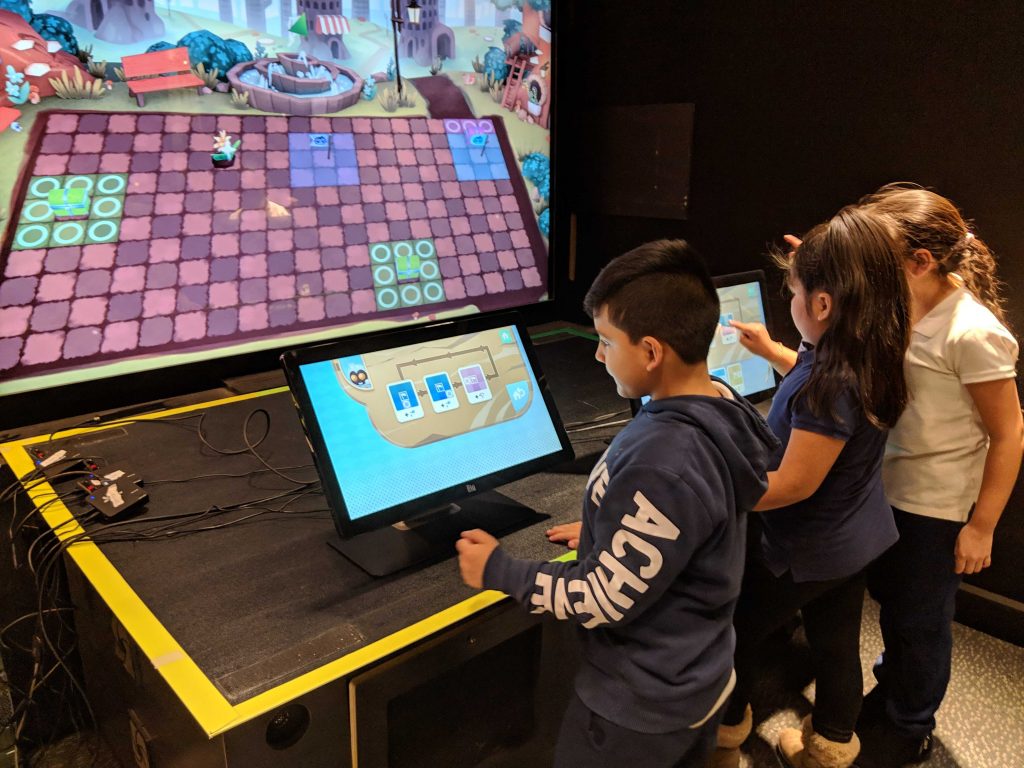

I recently had the opportunity to design a museum game called Rainbow Agents, which we created from the ground up with these three pillars at heart. In the game, players work together to create and maintain a community garden by cooperatively programming magical AI creatures. Rainbow Agents focuses on pro-social, constructive mechanics and has been incredibly successful with audiences who have traditionally been excluded from computer science and gaming.

Next Time…

After creating a foundation of mechanics that welcome diverse audiences, the next step is to design game features to support their specific needs. In future installments of the series, we’ll take a deep dive into topics like accessibility, representation, and more. Stay tuned!