Filament’s formal game development processes have benefited greatly from our Work-for-Hire business model. Throughout any given year a multitude of small projects have guaranteed rapid iteration on our ideas of how best to make games. I’ve always thought we’ve been reaching for the ideal. I was convinced that there was some process nirvana that was going to take many projects, many lessons, and many iterations to reach.

But as I’ve shepherded teams through our process, and as the stack of projects under Filament’s belt grows, the more examples I’ve seen of process limiting great work from exceptional developers. So here is my slow epiphany: As team experience increases, our adherence to concrete process needs to decrease. In order to make better games, we need to allow each team to make their unique mark on the development process.

Filament’s formal game development process

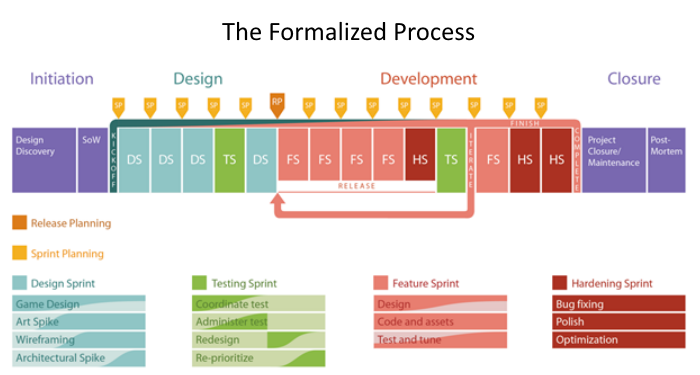

So what is our formal process and why do I want to change it? It’s difficult to label with just a word. I hesitate to call it anything recognizable. Even uttering the words Agile, Scrum, Kanban, or Waterfall will draw the ire of people who have their feet firmly planted in unchanging definitions. I would jokingly say we just stick post-its on the wall and move them from a TO DO column to a DONE column, but that’s not the case. Our process, when documented, is incredibly long and complex. There are steps at every point to ensure something critical doesn’t fall through. Picking it apart would be a lengthy exercise – and trust me I’ve been doing just that for seven years.

So I’ll simply say this; Filament’s game development philosophy manifested is the process of prioritizing, planning, executing, testing, and reflecting. Stick that format in a loop, while (game != done) and you’re golden. Sure, we’ve formalized this process with phases like design, pre-alpha, beta, etc. We have meetings: scrum, sprint planning, retrospective, and more. We’ve even been known to confirm resolve tasks and document entry/exit criteria. We send countless emails, meet with clients, chat over Slack, and document in JIRA, but at every point of the project we follow the five simple steps listed below.

Our agile-like process is good for a great many things. It gives us a common language for discussing what is working and what isn’t. We can make small adjustments to the framework without drastic changes to the larger whole. At any point in a project we can understand where a team is in the process. This is great for realignment of a team that’s fallen off track. If all teams are running the same process, no one requires retraining. With everyone studying from the same playbook, all questions have one clear answer. Process is great for any time we have to shuffle teams at Filament. It’s disorienting enough joining a new group and getting your hands on a project you’re unfamiliar with, but when that team is using the same process you just came off of you can find where you fit immediately. It’s clear that process creates a consistency that’s not only great for the old guard, but also for new hires as well. They can be trained by anyone and quickly gain a sense of understanding about how Filament operates.

There are two big drawbacks I’ve identified in agile’s process for making games – it doesn’t apply equally well to all projects, and teams with high levels of experience always want to change it to better suit their needs. One of these issues almost always follows the other. It’s a more experienced team that’s able to identify when process doesn’t serve a project and propose an alternative. Sometimes it’s small things, like a team feeling confident about limiting standups in order to focus on work. Other times changes can be much larger, like a project that can’t be tested by external QA. Using an agile methodology isn’t so much about responding to feedback and iterating on features as it is about being comfortable adapting a process you believe strongly in to better serve the project or teammates.

Adapting for more experienced teams

At Filament there’s a never ending quest to improve. In every project we take on there exists implicit goals of increasing efficiency and minimizing risk. We make tweaks to our process, big and small, but each time we invite a bit of risk. By allowing experienced developers to change process at a level lower than the company, we’re inviting a bit of chaos into the organization. We create scenarios ripe for unique problems. Team A’s adapted process could face an issue they have no defense against, while Team B avoided the problem entirely.

How are we to keep track of all these different ways of development? How can we compare them against one another when the members of the teams using them are completely different people. What works for one person certainly doesn’t work for everyone.

So what are the benefits? If we use our base as a structure to make specific tweaks that tackle the unique problems different projects bring, hopefully we’ll be better at making games (higher quality, on time, and under budget). At this point I’ve written a lot without making clear what changes I’d make as a developer. That’s because all teams are different. The changes I would make, I can guarantee someone else would freak out over. But since you’re asking, here are some of the things I would encourage:

1. Don’t formalize lines of communication. If your team is small, and you sit with each other, communication is happening all of the time. If you don’t know what a particular person has been up to for a few days you should probably ask them. Be wary of creating repeating meetings that enable people to get on the same page. Slotting communication into specific scrums can create weird side effects of people waiting until the next meeting to relay critical information. If it involves talking to a teammate, don’t delay! Just do it!

2. Seek feedback as soon as you’ve made a thing. A great way to make terrible stuff is to fill your sprint with 100% feature implementation with no room for iteration or polish. At best, process would tell you to log an improvement task and work on it next sprint. You can wait for a sprint assessment or review to get critical feedback. That’s being agile, right!? Problem is, you’re working on that feature right now! You’re thinking about it right now! It’s in front of you begging for a little bit more time. Do yourself (and the project) a favor and polish now. Current you is really bad at predicting when future you will realistically get back to that feature. Every improvement you knock out now is time and energy saved later.

3. Leadership can come from anyone, but the best leadership is culture. On an ideal team, everyone knows their role. An even better dynamic exists when everyone has an understanding of their teammates’ roles and how they fit in the larger picture. If your team as a unit isn’t judiciously seeking self-improvement in process and communication in an attempt to squash inefficiencies, someone needs to step up and commit. Practicing these skills is the first step to making it a habit for everyone on the team.

4. Speak up, listen. For many developers, they do what someone else told them and do it how they were told it needs to be done. This sort of delegation is ripe for opportunities of improvement. It’s likely no one knows how to do your work better than you, so speak up. Let your teammates know what would result in better work from you.

5. Rush to first playable. Your first goal should be an implementation of your core game loop. This flies in the face of what I call column-to-column development – picking a small group of User Stories (features) to complete each Sprint. Maintaining a steady pace from Kickoff to Alpha or Beta delivery leaves me feeling like we’ve started a number of features far too late. Being late means losing time and not enough time can translate to rushed features and unfinished implementations. Lack of iterations can ultimately make any promising game feel mediocre. Since I haven’t figured out yet how to micro our process for those critical few weeks at the start of a project, I usually throw it all out the window. Brute forcing some initial systems architecture and UI goes a long way to being able to accurately plan the rest of the project.

You can imagine saying trust me isn’t always the easiest pitch, but remember, you’re backing it up with experience. A record of delivering great games is the best offense when it comes to adapting the processes you use. For the developers out there, suggest an improvement in your next standup. Be prepared to talk about the problem you are facing and how your proposed solution will eliminate it.

For the producers, make sure you’re eliciting feedback on process from your teams – doubly so if you’re running multiple distinct teams. You can be the keeper of process, but they need to be the owners. Remember every team is different, and only they can truly say what best works for them.